Lonie Knight

Staff Writer

The Florida Supreme Court announced on Monday, Jan. 26 that ABA accreditation is not longer required for law schools in order for students to take the BAR exam. This former request has sparked debate over the future of legal education and professional standards in the state.

The ABA has been the main organization responsible for accrediting law schools whose graduates are eligible to take the Florida Bar Exam. The Florida Supreme Court has relied on the ABA’s standards. The Florida Bar News reports that Moody’s request asks the court to reconsider whether continuing to depend on the ABA is the best approach or if other accreditation options should be considered.

In early January, Texas made a similar notion, ending the ABA law school accreditation. In February 2025, the Trump administration threatened to render the accreditation obsolete unless programs pulled their diversity requirements.

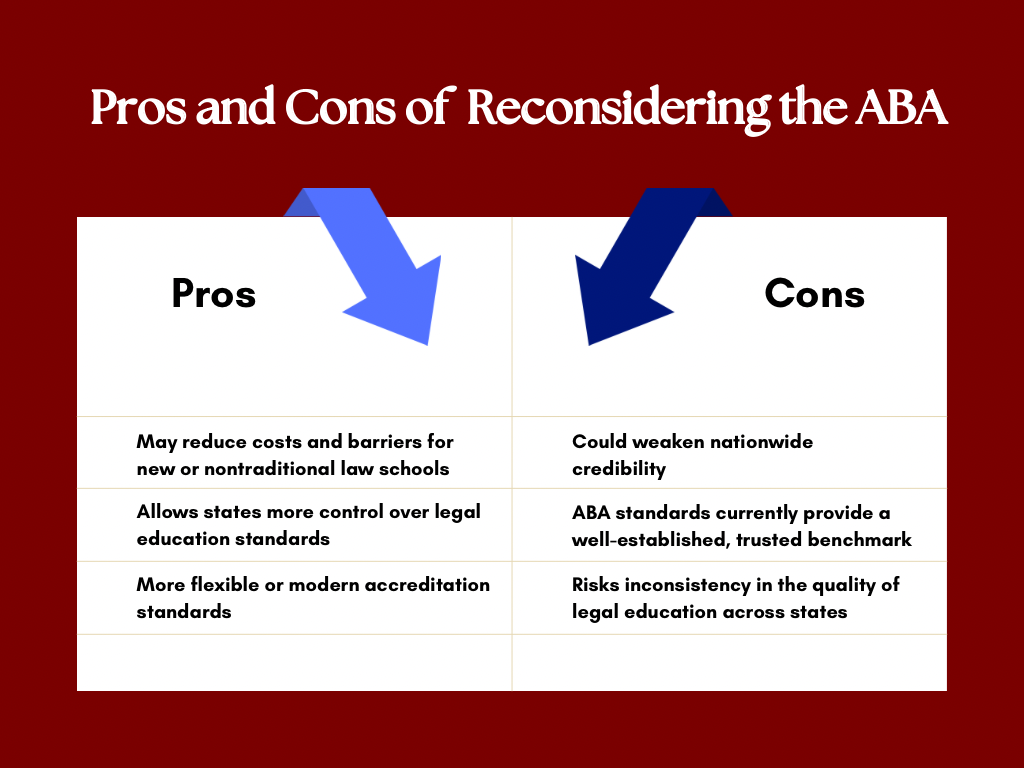

It’s further reported that the request challenges a long-standing rule requiring Florida Bar applicants to graduate from a law school accredited by the ABA. Supporters say reducing the ABA’s role could lower costs and give schools more flexibility, while critics argue it could weaken oversight and leave students uncertain about their career prospects.

The matter has drawn attention from educators, legal professionals and students, many of whom are watching closely to see how the court responds. While supporters frame the proposal as a way to modernize legal education and make it more accessible, opponents worry that changing the accreditation system could create uncertainty for both law schools and the students who depend on them to meet bar admission requirements.

FSC professor Dr. Bruce Anderson said the request is significant because it forces a closer look at how law schools in Florida are monitored and evaluated.

“It raises the question of the quality of legal education in certain schools in Florida,” Anderson said. “Accreditation exists to make sure students are being trained at a level that prepares them for real legal work.”

For students, the possible impact depends on timing. Anderson noted that pre-law students are unlikely to feel immediate effects because any change would take time to implement. Current law students, however, could face confusion if accreditation rules were altered while they are still enrolled.

The Florida Bar also reports on students often choosing where to enroll based on whether their degree will allow them to sit for the bar exam and compete for jobs after graduation.

Supporters of moving away from the ABA argue that its standards can drive up tuition and limit innovation in legal education. According to Anderson, it’s said that alternative oversight systems could create more affordable pathways and allow schools to adapt to changes in the legal profession. He mentioned critics warning that loosening standards could come at a cost.

Anderson said he believes the most realistic risk to be the emergence of poorly regulated law schools producing graduates who are unprepared to practice law.

“The greatest risk is having very poor law schools,” he said. “You could end up with people joining the legal community who have no business being there.”

Still, Anderson said there could be a potential upside if credible alternatives to the ABA emerge.

“It would surprise me if we did something that completely cut ties with the ABA,” Anderson said.