Julia Vorbeck

The Southern Editor

In the age of endless scrolling and algorithm-driven entertainment, one disturbing trend has quietly rooted itself into mainstream culture: children becoming the backbone of online content. Whether it’s the viral chaos of “The Rizzler,” the polished story-lines of family vlog channels or the multimillion-dollar empire built on Ryan’s Toy Reviews, kids are increasingly being placed in front of the camera not as participants, but as products.

And we’ve become far too comfortable with it.

Unlike traditional child actors, who work within a system governed (imperfectly) by child labor laws and trust requirements like the Coogan Act, children featured online have virtually no standardized protections. Their earnings aren’t guaranteed to be saved. Their hours aren’t monitored. Their consent, if given at all, is shaped by the fact that they often cannot fully understand what they’re agreeing to.

Family vlog channels in particular have created a new genre of entertainment: daily life turned into a monetized spectacle. Audiences watch toddlers open Christmas presents, cry during tantrums, navigate medical issues or celebrate milestones. These are moments that should belong to the children. But instead, they become thumbnails and revenue streams.

Parents often defend the practice by saying the kids “love the camera” or that the videos help families stay connected. But a child smiling for a video doesn’t mean they understand the permanence of the internet or the consequences of becoming the face of a brand before they can tie their shoes. What does it mean for a child to have millions of strangers watching their most vulnerable moments? What does it mean when their identity becomes intertwined with clicks, likes and sponsorship deals?

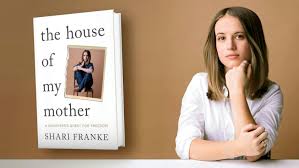

One of the most outspoken is Shari Franke, who grew up on her parents’ YouTube channel 8 Passengers. She now argues that family vlogging deprived her of a normal childhood. “There is no such thing as a moral or ethical family vlogger,” Frankie said to People magazine in an interview.

Shari has also shared deeply personal memories: being filmed while bra shopping at 18, for example, she said, felt “weird and inappropriate.” She also spoke about how children in these setups often cannot meaningfully consent.

“In any other context, it is understood that children cannot give consent, but for some reason, people think family vlogging is different,” Franke said.

Her brother, Chad Franke, also rejected the model. On ABC’s “Good Morning America,” he said, “I eventually want to have a family, and I’ve learned from my mom’s mistakes. We’re shutting off social media, shutting off the cameras. I’m not going to be using any kid as an employee.”

These voices are joined by former members of Piper Rockelle’s “Squad”, who are now publicly criticizing the environment they once lived in. In the Netflix docu-series “Bad Influence: The Dark Side of Kidfluencing,” teens say they were manipulated and pressured into stunts and “crush content” for views.

One former member, Sawyer Sharbino, said: “Eventually, it became you’re just being told what to do like you’re a puppet.” Another, Sophie Fergi, described feeling trapped: “There are so many videos that made all of us feel uncomfortable, some of the hardest years of my life, and I’m only 12.”

According to legal filings and interviews, their “momager,” Tiffany Smith, allegedly pushed the kids into provocative outfits, directed them to make out and orchestrated highly scripted content. After a lawsuit, Smith settled in 2024 for $1.85 million, though she and Rockelle deny wrongdoing.

These testimonies add real-world urgency to ethical concerns about child content creation. Unlike child actors working under strict labor protections, many kid influencers operate in a legal gray zone. Their earnings aren’t always safeguarded, their contracts are informal, and their right to refuse or erase content is limited.

The emotional toll, based on first-hand accounts, can be profound: exploitation, emotional manipulation and loss of autonomy. Shari Franke’s story even helped prompt legislation in Utah to protect child creators and require trust accounts for their earnings.

As consumers, we’re part of this ecosystem: every click, like and share drives the demand. If we truly care about the well-being of children, we need more than just regulation; we need a cultural shift. It’s not enough to watch less; we must demand better. We should support calls for labor protections, financial safeguards, and giving children a voice in how their childhoods are shared.

Childhood isn’t content. It’s not for sale.